'Boriswave' dependants set to cost UK £35bn by 2028

Over 530,000 dependants entered the UK under the last Conservative government. By 2028 they will have cost the UK economy £35bn.

Research by the Centre for Migration Control has found that the Conservative Party’s 2021 decision to allow skilled workers to bring dependants with them will have cost the UK £34.7bn by 2028.

Using official figure from the Office for Budgetary Responsibility, the CMC has input data gathered from the Home Office via freedom of information requests to determine the costs associated with this decision, which allowed 533,523 dependants to arrive in the UK between 2021 and the July 2024 general election.

Bacckground

In 2020, announcing their plans for the post-Brexit immigration system, the Conservative Party made it clear that “skilled workers and postgraduate students will continue to have the right to bring dependants”.

They estimated that this decision would increase the number of dependants arriving in the UK by between 5,000 and 20,000 but were warned by Migration Watch UK that this estimate “risks grossly understating the potential impact”.

The result was that between, January 2021 and June 2024, over 500,000 migrants arrived in the UK as dependants.

In January 2024, recognising the error of allowing all skilled workers and students to bring dependants, the Conservative government reversed this decision.

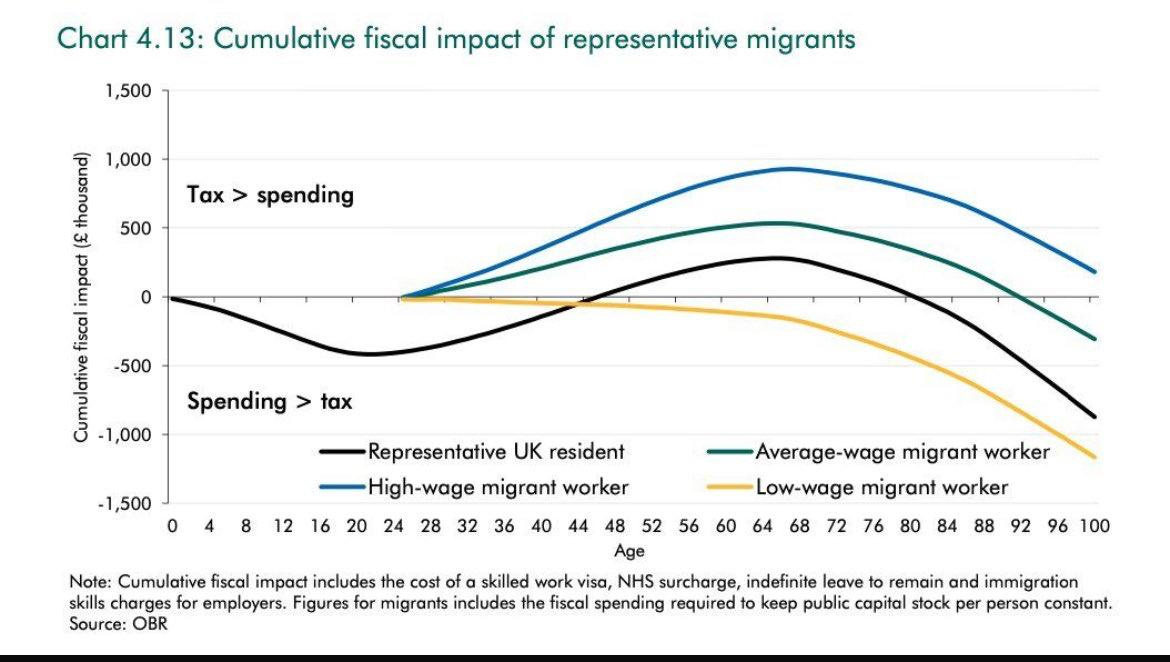

In September 2024, the OBR released a much-publicised Fiscal Risk report which showed, for the first time, that low-risk migrants are a net cost to the Exchequer at every stage of life.

However, a key omission of this study was that the OBR “opted to model a more typical migrant on a work visa and no dependants”.

This decision was criticised by Karl Williams of the CPS who said the OBR had used “some questionable assumptions in the new modelling, for example ignoring dependants”.

Matt Goodwin, also said that “the OBR bizarrely assumes migrants have no dependants or relatives”.

Child dependants

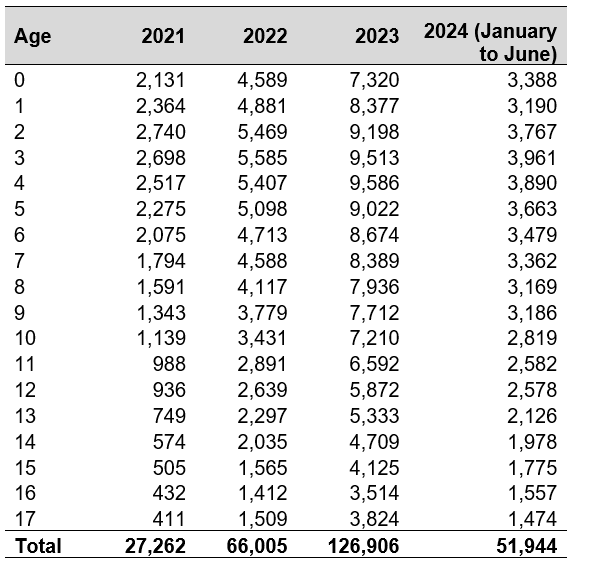

the CMC submitted an FOI request to the Home Office, requesting a breakdown of all child dependants by age. Using the OBR assumption that “the fiscal impact of a child dependant is likely to be similar to that of the representative UK person” and the information provided to the CMC via FOI, we are able to calculate the expenditure on child dependants.

The Home Office and OBR figures are also cross referenced with Migration Advisory Figures on the attrition rate of non-EU migrants (how long they stay in the UK before leaving).

Number of Child dependants arriving in the UK, broken down by age:

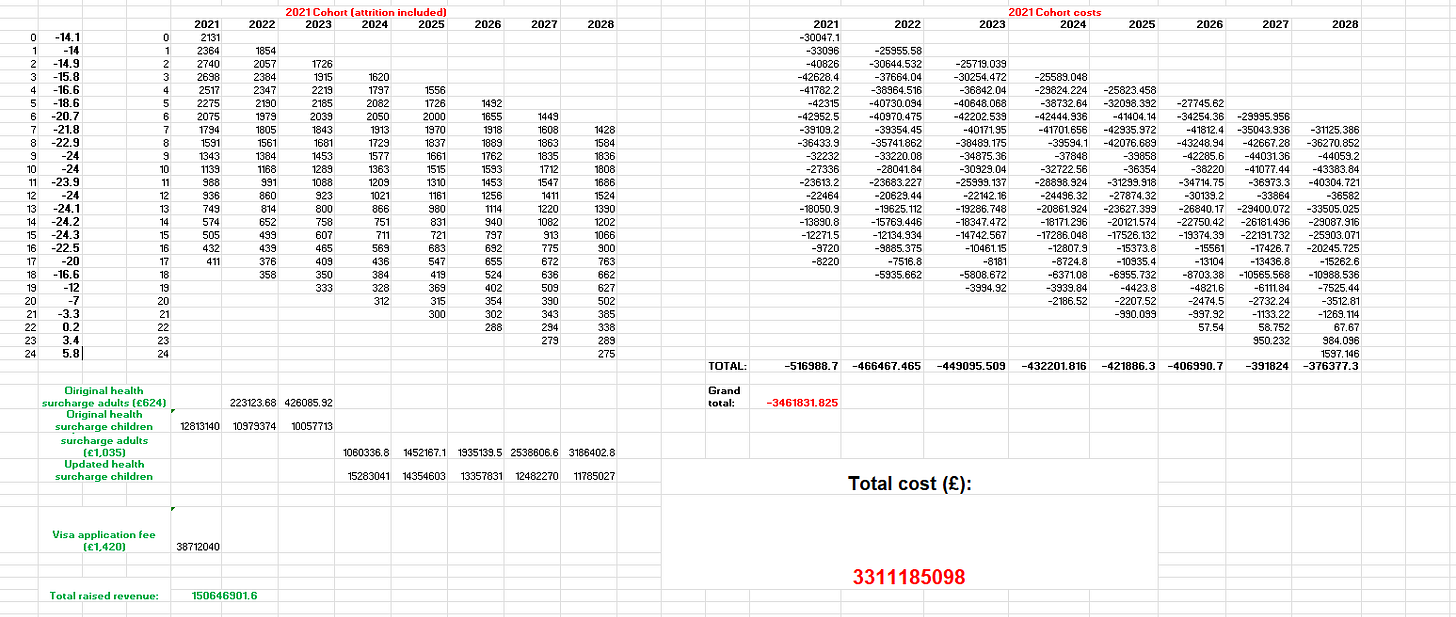

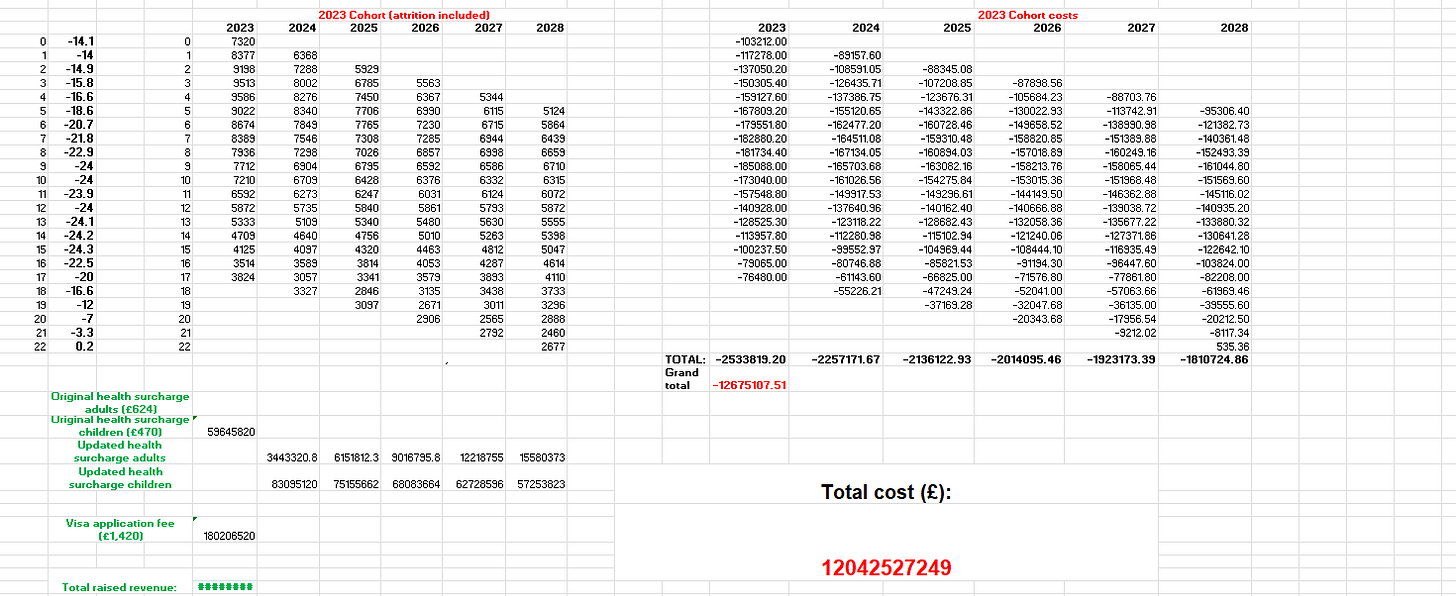

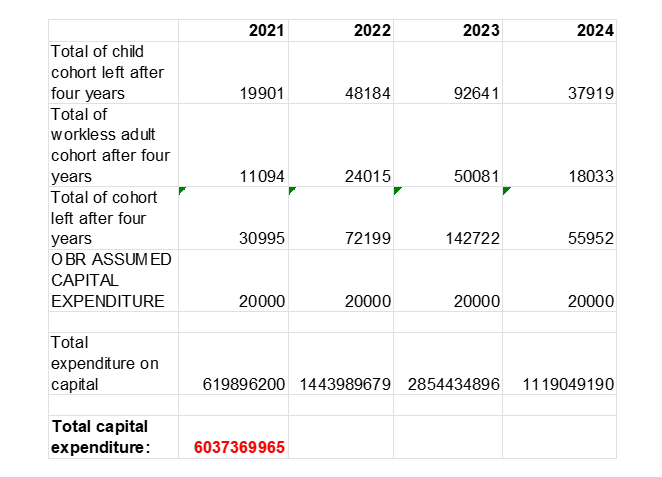

2021: By 2028 (the end of the OBR’s projection forecast) the child dependants who arrived in the UK, will have cost the Treasury £3.46bn and raised in revenue (through visa application costs and IHL) £38.7m. This will mean that the net cost to the UK is: £3.3bn

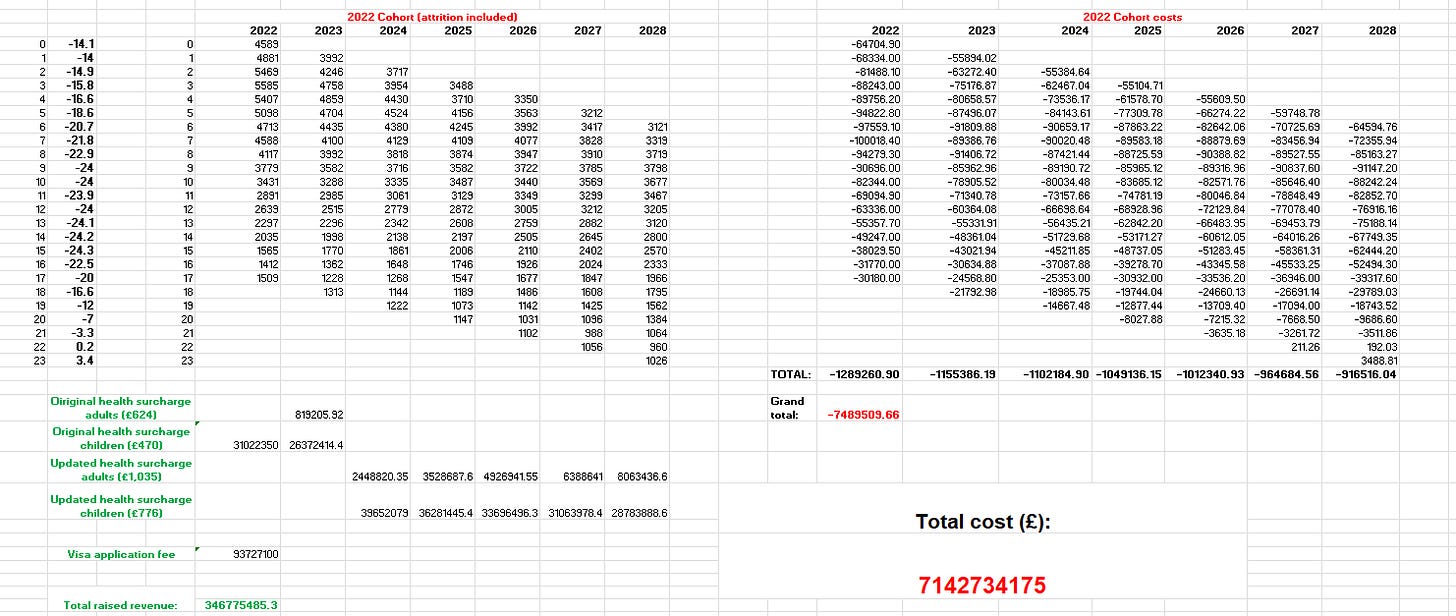

2022: By 2028, those who arrived in the UK in 2022, will have cost the UK £7.4bn, and raised in revenue £346m. The net cost to the UK is £7.1bn.

2023: By 2028, those who arrived in the UK in 2023, will have cost the UK £12.6bn, and raised £632m. The net cost is £12.04bn.

2024: By 2028, those who arrived in the UK in the first six months of 2024, will have cost the UK £4.4bn, and raised £245m. The net cost is £4.19bn.

Adult dependants

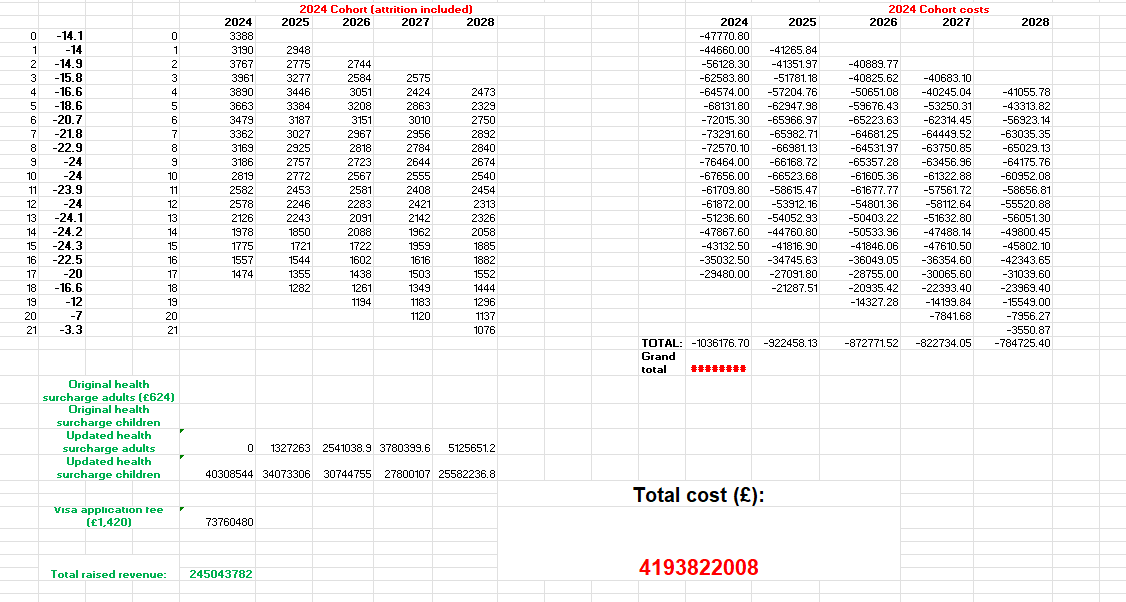

A Home Office FOI released in May 2024 shows that the Home Office’s assumption is that just 46% of adult dependants accompanying someone on a Health and Social Care Visa will take on employment.

Using Home Office data provided to the CMC in November 2024, we can make the following forecast as to the number of adult dependants who remain out of work:

The OBR assumes that an average working migrant – arriving in the UK at 25 – will have around £9/10 thousand pounds per year spent on them.

The spending pattern for a dependant workless migrant will be the same, but the tax take will be substantially less than the amount assumed by the OBR (as they are workless, they will not be paying income taxes and will only be paying indirect taxes such as VAT and fuel duty).

The Centre for Migration Control has used ONS figures on the average amount spent per household on indirect taxes, broken down by quintile. The decision was taken to use the third quintile (above the average median wage), and therefore is likely an over assumption of the amount of revenue being raised: Effects of taxes and benefits on UK household income - Office for National Statistics

Further, the CMC has decided to attribute all indirect taxes paid per household to the workless adult dependant – a decision which, again, means the average revenue from these migrants is likely to be an overestimate.

According to the OBR, for their first seven years in the UK, a workless adult dependant will have spent by the state: £7600 in year one, £7600 in year two, £7600 in year three, £7700 in year four, £7700 in year five, £9600 in year six, and £9700 in year seven. It is important to note that the reason for the lower costs in years one to five is because this is when the OBR includes the money raised via visa applications and Immigration Health Surcharges by migrants.

If we apply these figures to the 15,197 adult workless dependants who arrived in 2021, and adjust for the MAC’s attrition rate, the total cost of this group the Treasury by 2028 will be £786m, and will raise via revenue (indirect taxes) £461m, leaving a net cost of £324m.

In 2022 there is a significant increase in the number of adult workless dependants, of 32,898. Their total cost to the Treasury by 2028 is £1.4bn, raising £893m, with a net cost of £593m.

In 2023, the 68,604 migrants impose a gross cost of £2.6bn by 2028, raise £1.6bn via indirect taxes, and therefore have a net cost of £1.01bn.

Between January and June 2024 there were 24,703 dependant adults, who are workless, let into the UK by the Conservative government. Their gross cost by 2028 will be £786m, raising £503m, and therefore a net cost of £283m.

Capital Costs

The final consideration is the amount that capital spending needs to be increased to deal with the surge in population (given that 100% of the UK’s population increase now comes from immigration, these are costs that would not have otherwise been incurred by the existing British population).

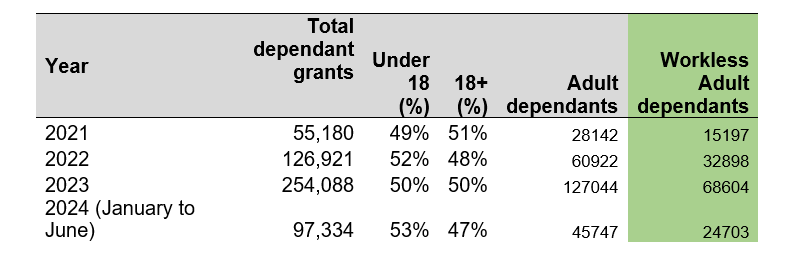

The OBR, in its fiscal risks report, assumes that – over a four-year timeframe between 2024 and 2028 – the costs of increasing the UK capital stock for each migrant will be £20,000.

Although this is a figure that will have been accumulated over each year that a dependant is in the UK, and is likely to be higher for children who require additional spending on classrooms, healthcare etc, the CMC only applies the cost to those migrants from each cohort who have remained for at least four years. This means that, because of the attrition rate factored into our modelling, there are many migrants who will have lived in the UK for, say, three years but will not have had any capital costs attributed to them. This is a conservative means of calculating the total spending that is needed for capital stock, as it is undeniable that a migrant – even if they are only here for a year or so – will have required some for of capital expenditure to cater for their presence in the UK. Of course, the alternative is that the government does not increase capital expenditure at all to cater for the increased population caused by mass migration - a decision which, if taken, would lead to a huge slide in living standards for Brits.

The final consideration is the amount that capital spending needs to be increased to deal with the surge in population (given that 100% of the UK’s population increase now comes from immigration, these are costs that would not have otherwise been incurred by the existing British population).

The OBR, in its fiscal risks report, assumes that – over a four-year timeframe between 2024 and 2028 – the costs of increasing the UK capital stock for each migrant will be £20,000.

Although this is a figure that will have been accumulated over each year that a dependant is in the UK, and is likely to be higher for children who require additional spending on classrooms, healthcare etc, the CMC only applies the cost to those migrants from each cohort who have remained for at least four years. This means that, because of the attrition rate factored into our modelling, there are many migrants who will have lived in the UK for, say, three years but will not have had any capital costs attributed to them. This is a conservative means of calculating the total spending that is needed for capital stock, as it is undeniable that a migrant – even if they are only here for a year or so – will have required some for of capital expenditure to cater for their presence in the UK.

The calculations have been set out below:

Other conservative assumptions taken by the CMC, meaning the figure is likely an underestimate, are that dependants of those on Health and Social care visas are exempt from the Health Surcharge - we have still included this revenue stream. Similarly, as individuals approach five years in the United Kingdom they become eligible for settled status, a position which then affords them rights to benefits - and would thus add further fiscal strain.

ENDS